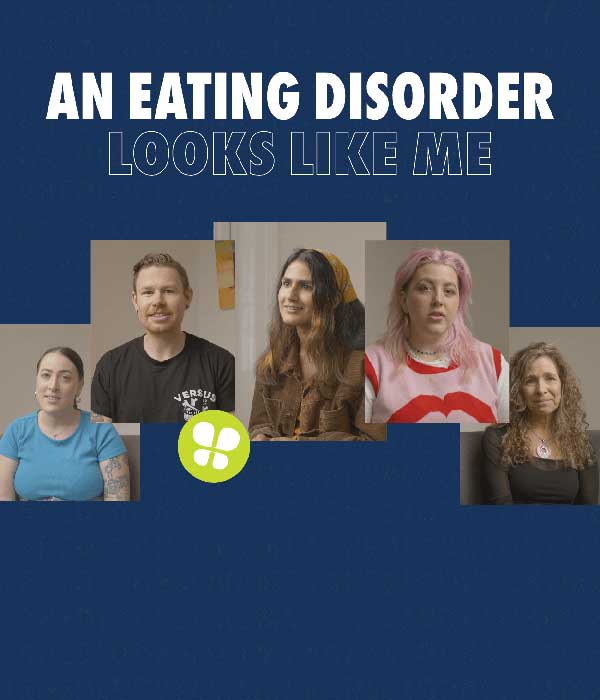

The article below is courtesy of Health Direct Australia. Please visit them for qualified advice on a wide range of health-related issues. If you suspect that you might have an Eating Disorder, please visit your local GP.

What is an eating disorder?

An eating disorder is a serious mental health condition that involves an unhealthy preoccupation with eating, exercise or body shape.

Anyone can develop an eating disorder, regardless of cultural background, gender or age. Eating disorders are estimated to affect approximately 4 in every 100 people in Australia (or about 1 million people in Australia). About 1 in 7 people experience disordered eating in their lifetime.

If you have an eating disorder, you may experience any of the following:

- A preoccupation and concern about your appearance, food and gaining weight.

- Extreme dissatisfaction with your body — you would like to lose weight even though friends or family worry that you are underweight.

- A fear of gaining weight.

- You let people around you think you have eaten when you haven’t.

- You are secretive about your eating habits because you know they are unhealthy.

- Eating makes you feel anxious, upset or guilty.

- You feel you are not in control around food.

- You keep checking your body — for example, weighing yourself or pinching your waist.

- Making yourself vomit or using laxatives in order to lose weight.

What are the common types of eating disorder?

There are several types of eating disorder, including:

Binge eating disorder (BED)

BED makes up almost half of all cases of eating disorder in Australia. People suffering from this disorder will frequently consume very large quantities of food, even when they are not hungry (known as ‘binging’). They often feel shame and guilt after an eating binge; however, unlike people with bulimia nervosa (see next section), they do not purge their food. It is common for people with binge eating disorder to fast or go on diets in response to the way they feel after a binge.

Bulimia nervosa

People with this disorder have frequent eating binges, often in secret, then get rid of the food through vomiting, laxatives or diet pills (known as ‘purging’). People with bulimia often feel out of control. About 1 in 10 people with eating disorders have bulimia nervosa.

Anorexia nervosa

Less than 1 in 100 people in Australia has anorexia nervosa. People with this condition can be severely underweight, are preoccupied with food and fear putting on weight. They often have a distorted body image and see themselves as fat. People living with anorexia nervosa may create extreme rules and restrictions about their diets and exercise schedules.

Other specified feeding or eating disorder (OSFED)

A person with OSFED has many of the symptoms of other eating disorders but their condition doesn’t align with any specific disorder. People with OSFED commonly have very disruptive eating habits and can have a distorted body image. Around 1 in 3 people who seeks treatment for an eating disorder have OSFED.

What are the symptoms of eating disorders?

It is not always easy to tell if someone has an eating disorder, since they may try to hide it because of shame or guilt. However, some of the behaviours associated with eating disorders include:

- Dieting: this could mean calorie (kilojoule) counting, fasting, skipping meals, avoiding certain food groups or having obsessive rituals related to eating.

- Binge eating: including hoarding of food or the disappearance of large amounts of food from the kitchen.

- Purging: vomiting or using laxatives to rid the body of food. People who purge often make trips to the bathroom during or after eating.

- Excessive exercise: a person may refuse to disrupt their exercise routine for any reason, insist on doing a certain number of repetitive exercises or become distressed if unable to exercise.

- Social withdrawal: the person may avoid social events and situations that involve eating, or they prefer to eat alone.

- Body image: the person may focus on body shape and weight.

- Change in clothing style: the person may start wearing baggy clothes, for example.

There are also physical signs that a person may have an eating disorder, such as:

- Weight changes: fluctuations in weight or rapid weight loss.

- Disturbed menstrual cycle: loss of or disrupted periods.

- Dizziness: feeling light-headed or faint.

- Fatigue: constantly feeling tired.

- Being cold: sensitivity to cold weather.

- Inability to concentrate (or think rationally).

Some of the emotional signs of an eating disorder include:

- Obsession with weight: preoccupation with weight, body appearance or food.

- Low self-esteem: feelings of low self-worth or a negative body image.

- Negative emotions: anxiety, depression and feeling that life is out of control.

- Meal-time anxiety: feeling anxious, upset or guilty in relation to food.

- Mood changes: depression or anxiety, moodiness or irritability.

CHECK YOUR SYMPTOMS — Use the Symptom Checker and find out if you need to seek medical help.

What causes eating disorders?

It is unlikely that an eating disorder has one single cause. It’s normally due to a combination of many factors, events, feelings or pressures. A person might use food to help them deal with painful situations or feelings without realising it.

These factors may include low self-esteem, problems with friends or family relationships, problems at school, university or work, high academic expectations, lack of confidence, concerns about sexuality, or sexual assault or emotional abuse.

Traumatic events can trigger an eating disorder, such as the death of someone special (grief), bullying, abuse or divorce. Someone with a long-term illness or disability (such as diabetes, depression, vision impairment or hearing loss) may also have eating problems.

Studies have shown that genetics may also be a contributing factor to eating disorders.

How are eating disorders diagnosed?

Many people who suffer from eating disorders keep their condition a secret or won’t admit they have a problem. However, it’s important to get help early (see, ‘Where to get help’).

The first step is to see your GP, who can refer you to the appropriate services. A doctor or mental health professional will make a diagnosis.

There is no single test to determine whether someone has an eating disorder, but there is a range of evaluations that lead to a diagnosis, including:

- Physical examinations: Disordered eating can take a toll on the body, so the doctor must first check the person is physically OK. The doctor is likely to check height, weight and vital signs (heart rate, blood pressure, lung function and temperature). They may also check blood and urine.

- Psychological evaluations: A doctor or mental health professional may talk to the person about eating and body image. What are their habits, beliefs and behaviours? They may be asked to complete a questionnaire or self-assessment.

Treatments for eating disorders

Starting treatment as early as possible is important because there can be long-term health consequences for people with chronic eating disorders.

There is no ‘one size fits all’ approach to treating eating disorders since everyone is different. Often a team of health professionals is involved in an individual’s treatment, including a psychologist, dietitian and doctor.

Some of the treatment options include:

Counselling

This involves regular visits to a psychologist, psychiatrist or other mental health counsellor. Counsellors use different methods to help people with eating disorders. A common method is ‘cognitive behavioural therapy’ (CBT), which helps individuals identify and change the thoughts, feelings and behaviours associated with their eating disorder.

Nutrition education

A dietitian can help a person with an eating disorder learn healthy eating habits and return to a normal weight. For a person with anorexia nervosa, this is essential and could include education about nutrition, meal planning, establishing regular eating habits and ways to avoid dieting.

Family approach

The ‘family approach’ is most common when young people are being treated for an eating disorder. The aim is to treat the person with the eating disorder, while also supporting and educating the entire family — which strengthens family relationships. The family learns how to better care for the person with the eating disorder.

Medication

There is no medication to specifically treat eating disorders. However, a person with an eating disorder may be prescribed medicines to treat other symptoms. Antidepressants are sometimes used to help reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety. Medications should be used in conjunction with other treatment approaches.

Person-centred, stepped care

Person-centred, ‘stepped care’ is a treatment that’s tailored to suit that person’s illness, situation and needs. Stepped care recognises that people with eating disorders may need to move ‘up and down’ through various levels of care throughout their illness.

With the right professional, social and emotional support, a person with an eating disorder can recover.

What should I do if I think I have an eating disorder?

People with an eating disorder may feel it helps them stay in control of their life. However, as time goes on, the eating disorder can start to control them. If you have an eating disorder, you may also have the urge to harm yourself or misuse alcohol or drugs.

Talk to someone you trust — such as a close friend or family member — if you think you have an eating disorder. You can also call the Butterfly Foundation National Helpline (1800 33 4673, 8am to midnight AEST, 7 days a week). You can also call the Butterfly Foundation for advice if you’re concerned about a family member or friend.

Your doctor can advise you on diagnosis and possible treatment options, which will depend on your individual circumstances and the type of eating disorder you have.

Where to get help

If you or someone you know has the symptoms of an eating disorder, it is important to seek professional help as early as possible. Eating disorders are damaging to the body and can even be fatal but they are treatable.

Visiting your doctor is the first step to recovery. If you don’t have a GP, you can find one near you using the healthdirect Service Finder.

You can speak confidentially to an adviser on the Butterfly Foundation National Helpline (1800 33 4673, 8am to midnight AEST, 7 days a week).

You can also call Eating Disorders Victoria for advice, support and information on 1300 550 236 (or email: edv@eatingdisorders.org.au).

If you are in crisis and need counselling now, you can call:

- Lifeline — 13 11 14 (24 hours)

- Suicide Call Back Service — 1300 659 467 (24 hours)

- 1800 Respect — 1800 737 732 (family violence or sexual assault)